Introduction to Palliative Care

As I mentioned I heard from my mum that an anesthesiologist from Calicut had been nominated for a Nobel prize for his work in community palliative care, so I headed back to my grandparents’, hoping to learn more about this community initiative and its success. I was attempting to change my study more towards looking at the movement of citizenship away from rights and more towards active responsibilities…development from below…or something like that. I took a taxi down the mountain from Mcleodganj and then boarded the small proper plane headed towards Delhi. Delhi airport was a cosmopolitan wonder. I was not used to seeing so many foreigners in India as they weren’t many in Kerala. I had a beer and a club sandwich (which was incredible as all club sandwiches are in India). I was already missing Dharamsala, it was cooler than the rest of India, and had a special calming aura about it, also the Korean and Japanese restaurants there were absolutely fantastic. I wondered if I had made the right choice in abandoning the Tibetan issue and choosing to go back to Kerala. After a brief nap, I boarded the plane towards Cochin. This was followed by a bus and a car ride until I was finally back in Calicut.

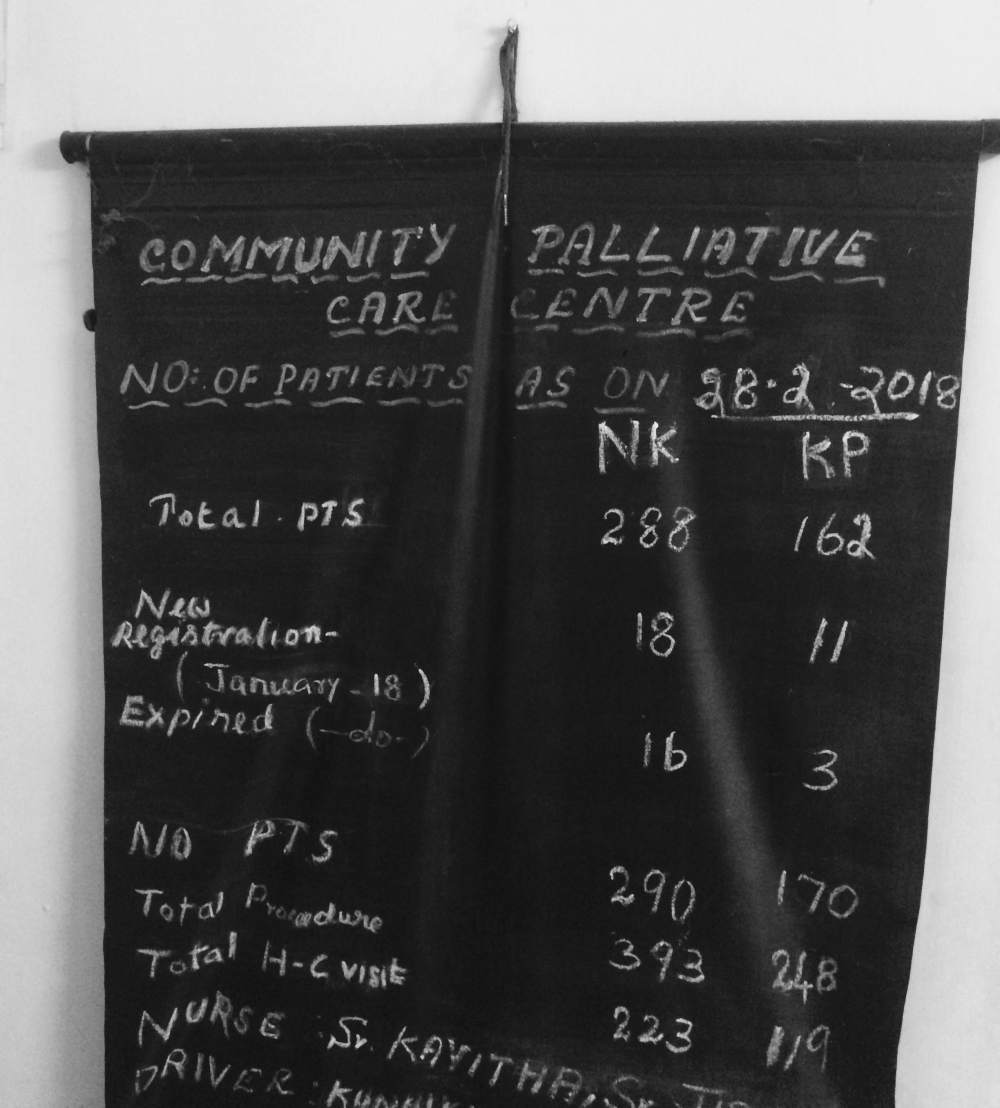

I woke up early the next morning so I could catch the local doctor at the Sparsham Palliative Care Society outlet near my home before he started off on his rounds. I was told that he’d be leaving for his once-a-week patient visits at around 9:30 am. I took an autorickshaw, which has fast become my favourite form of transport, and arrived at the centre just after 9. The centre was at present simply a house that had been rented out by the palliative care society. There was a welcoming room with a desk and two plastic chairs in front of it, where the doctor was seated. Behind that was a room where medical apparatuses, such as bedpans and cotton swabs, were being sterilized. The room to the right housed the computer and some wheelchairs that had been donated along with a bed. It was the kind with the adjustable angles that is common in hospital wards. I learned that this bed had also been donated and would be given to the patient who was deemed to be most in need of it. The small room off to the left of the welcoming foyer held the medicine and was where the food kits were assembled. The room was busy, and I was told this was because this was the one day a week that the doctor was in house. There was a fan spinning in the centre of the room but its coolness didn’t reach the far end of the room. I was already hot, and the sense nervousness added to the heat. Sweat began to drip down my back as I waited in the back until he had spoken to all the visitors.

As this was my first interview I made a few choices. I decided not to record the conversation as this was the first time I was meeting the doctor and didn’t want to intimidate him, although, in reality, I was the one who was intimidated. I had my notebook with me and a few ideas that I wanted to talk about, but I let the conversation take its own route. I had only corresponded with him through email, so I started off by clarifying who I was and what I was trying to do. Looking back at my notes I wish I had recorded the interview. I think I started off the interview by asking him if this program was filling a gap left by the inadequacies of the government- an idea that had been at the centre of my thoughts. He said that this was not necessarily the case and that there was an opportunity for government programs to be supported by community-based initiatives. He said it was essential that citizens ‘do things on their own’ in a place like this, and that the government was seeking public community help.

Even though the palliative care centre was run totally on donations without any government funds, there was a local government program to identify disabled persons in the community as a kind of census. This allowed for the public to react immediately in the case of palliative care. This allowed for what he called ‘spontaneous, yet organized help’. The community care centre was a way in which citizens could work as a group to provide the needed help which the doctor felt was more effective than working as individuals. Society in Kerala has strong family values and people were already taking care of the elderly and those with terminal illnesses on their own, be it family or neighbours, but this centre allowed for it to be carried out in a more organized and effective fashion. People were already doing good practice without being aware of it as ‘participatory citizenship’. This reminded me of the case of the Noordoostpolder in the Netherlands, where residents were already performing good energy practice without necessarily seeing it as such.

I then went on to ask the doctor if he knew what the reasons were behind people volunteering at the centre and the larger program that covered the entire city. He replied that they all had different reasons, but the important thing to note was that the public was sensitized. He said that Kerala was particularly good for this because the state has the highest literacy rate in India and has a long history of social movements. It came to my attention that a major factor in the idea of citizenship from below was a sensitized public. “If the people are aware, they can make a difference.” The doctor remarked on how in other states these kinds of initiatives were carried out by NGOs or private organizations whereas here it was done by the public themselves.

The doctor went on, without me prompting him, to say that this (palliative care) was a social issue so we have to look for social solutions. The medical system cannot provide support for things like losing a job, losing mobility, social stigma, and the loss of other things that result from such illnesses. What these individuals need the most is emotional and social support, and what gives rise to an effective social movement is people who are trained and empowered. The society’s goal in a way was to demedicalize illness, and as a public society, the idea is it will be able to maintain quality and standards. He went on to say that charity in the form of just money has limitations, and that actually performing activities does not have those same limitations. I asked him what drew him towards the issue of palliative care.

He said for him it was a rights-based issue- the right to life with dignity. With every population ageing, it is inevitable that they will need care. The problem with chronically ill patients is that it is a long drawn out process, and the challenge is how much can actually be corrected. He felt the people who volunteer and work at the society are aware of their potential and the idea has always been to teach them basic skills so that they feel that they are empowered. This idea was not limited to palliative care and could be extended to any public society. He said that he was making an investment in his own future, not necessarily just performing charity work, and that everyone involved with the program was doing the same. His responsibility was to see that this initiative sustains itself until then.

In terms of how the society worked, the money was mobilized by the community. He said the idea of volunteers was different from the west in that there they are there to fill in gaps. The idea here is to have the volunteers lead the program, and that they have a sense of ownership. Moreover, this sense of community ownership is integral and is what sustains the program. He concluded by saying that if the community leads the program, then they see all illnesses as suffering even though palliative care was started as part of cancer care. It was then time for him to leave on his rounds, and make his weekly visits to the scheduled patients in the community. I left as well after having organized an interview with the secretary of the society in the afternoon.

I returned later to interview the secretary of the society, a Mr Soman. It was not as busy, as the doctor was no longer there. Again I had chosen not to record the interview and to rather take notes as he spoke. I somehow found this more attuned to the situation. I wanted to learn the inner workings of the initiative from him and to get a general idea of what it looked like in practice before seeing it for myself. Rather than an interview, it was more Mr Soman talking, with a few interspersed questions from me, and honestly, I felt this was more informative than some kind of Q and A session would’ve been. He started off by telling me that everything at the society is done by the citizens, with no help from the government or corporation.

There were between 10 and 20 volunteers at any time, and they were all retirees. Their activities included administrative work, going on home visits, distributing pamphlets/raising awareness, and raising funds. I asked him why all the volunteers were retirees and he replied that the youth were not really interested in such initiatives. He said that there were some high school aged volunteers who would come from time to time as part of their involvement in the National Social Service, or scouts. Together with the kids, they did some coin box collections, and other methods of fundraising included placing money boxes in shops that allowed them. I asked him what moved him to join the cause, and he told me that he became aware of it when the society started a bank account at the branch that he was managing and that after retirement he had free time so he decided to join. There didn’t seem to be any sanctimonious reason for him participating, he just felt he was doing his part as a citizen.

His major axe to grind was that, according to him, there was no interest from the government in helping the cause. He also went on to emphasize that the society had no religious or political affiliation. Their biggest challenge at present was funding. They wanted to have their own building, where they could have in-house OP, physiotherapy, as well as just a daycare kind of place for affected people where they could mingle with one another. This is because a major cause of distress for them is loneliness and a lack of social interaction. I reflected on the old age homes I had volunteered at in Canada and just more generally on how there always seemed to be some kind of forum for the disabled or elderly to interact with each another and others, be it an old age home, strip mall, coffee shop or anywhere else. A major inhibitor to this in Calicut that came up in later interviews was the problem of mobility within the city. It is not an easy city to move around in if you have any kind of physical limitation. I organized to shadow the volunteers on a home care visit in the following days and left to reflect on the information I had gathered.

I started the day off by posting up at a cafe down the street from my guesthouse- Cafe Budan. I didn’t have much of a clue what I was actually going to research so I used the free wifi on offer to read up on some academic papers to try and develop a theoretical framework for my thesis. The menu in this place was pretty western- Indian filtered coffee was replaced by espressos and cappuccinos, while gluten-free cakes and chocolate croissants lined the pastry display in the front. It definitely appeared as though they were catering to a particular kind of customer and I probably wasn’t it. The guys working the counter spoke English really well and treated most of the foreigners who came in with a warm familiarity which led me to believe they were regulars. When I walked in, there wasn’t a single Indian customer in sight. A group of foreigners who spoke English with some sort of European accent sat on one of the tables outside. Beside me sat two Thai men: one dressed as a monk and the other in plain clothes. The monk was counting prayer beads on a string with his hand while conversing with his friend. Across from them a picture of the Dalai Lama hung high on the cafe wall. I thought that the monk might be on some sort of spiritual pilgrimage or perhaps he lived here now. The place had a distinct international flavour to it, as did the entire town- you could easily forget that you were in fact in India. An older foreign man was sitting outside, with a rolled cigarette in his hand, talking to one of the guys who worked in the cafe. A few of the people walking by shook hands with the cafe workers lounging out front. There was certainly an aura of community about the place.

I started the day off by posting up at a cafe down the street from my guesthouse- Cafe Budan. I didn’t have much of a clue what I was actually going to research so I used the free wifi on offer to read up on some academic papers to try and develop a theoretical framework for my thesis. The menu in this place was pretty western- Indian filtered coffee was replaced by espressos and cappuccinos, while gluten-free cakes and chocolate croissants lined the pastry display in the front. It definitely appeared as though they were catering to a particular kind of customer and I probably wasn’t it. The guys working the counter spoke English really well and treated most of the foreigners who came in with a warm familiarity which led me to believe they were regulars. When I walked in, there wasn’t a single Indian customer in sight. A group of foreigners who spoke English with some sort of European accent sat on one of the tables outside. Beside me sat two Thai men: one dressed as a monk and the other in plain clothes. The monk was counting prayer beads on a string with his hand while conversing with his friend. Across from them a picture of the Dalai Lama hung high on the cafe wall. I thought that the monk might be on some sort of spiritual pilgrimage or perhaps he lived here now. The place had a distinct international flavour to it, as did the entire town- you could easily forget that you were in fact in India. An older foreign man was sitting outside, with a rolled cigarette in his hand, talking to one of the guys who worked in the cafe. A few of the people walking by shook hands with the cafe workers lounging out front. There was certainly an aura of community about the place.